MAURA CHEN ON ARCHITECTURE OF THE KITCHEN THRESHOLD: IN SERVICE

The design of our spaces are often the physical manifestations of societal hierarchies, from the Israeli West Bank barrier to the design of restaurants. What is manufactured and composed has a way of absorbing these hierarchies, whether it be into the organization of governments or the framing of histories. Here, Maura Chen analyzes the restaurant architecture of Manhattan’s Chinatown.

“Americans have grown ever more estranged from the sources of their food and the largely unseen labor required to produce it,” writes Ligaya Mishan.(“The Activists Working to Remake the Food System: They’re committed not just to securing better meals for everyone, but to dismantling the very structures that have long exploited both workers and consumers”. The New York Times. 19 Feb 2021.) “Invisible people” Francis Lam identified in 2018, “often anonymous cooks and growers, who are largely immigrant or underrepresented communities, fuel this industry that now has so much cultural cache.”(“Food Stories that Don’t Pay The Bills”. The Racist Sandwich. 2018.) In the context of restaurants, this “cache” includes high profile chefs, display kitchens, farm-to-table dining, the rise of fast casual restaurants; all have contributed to a pre-pandemic neoliberal culture in which food consumption and production is largely regarded as de-politicized and post-class. But the design of buildings and urban infrastructure has long separated laborers from employers, suppliers from consumers, service workers from individuals being served. Architects are incentivized to showcase commodities and promote consumption, actively hide the realities of labor and production, and reinforce existing social division and hierarchy.

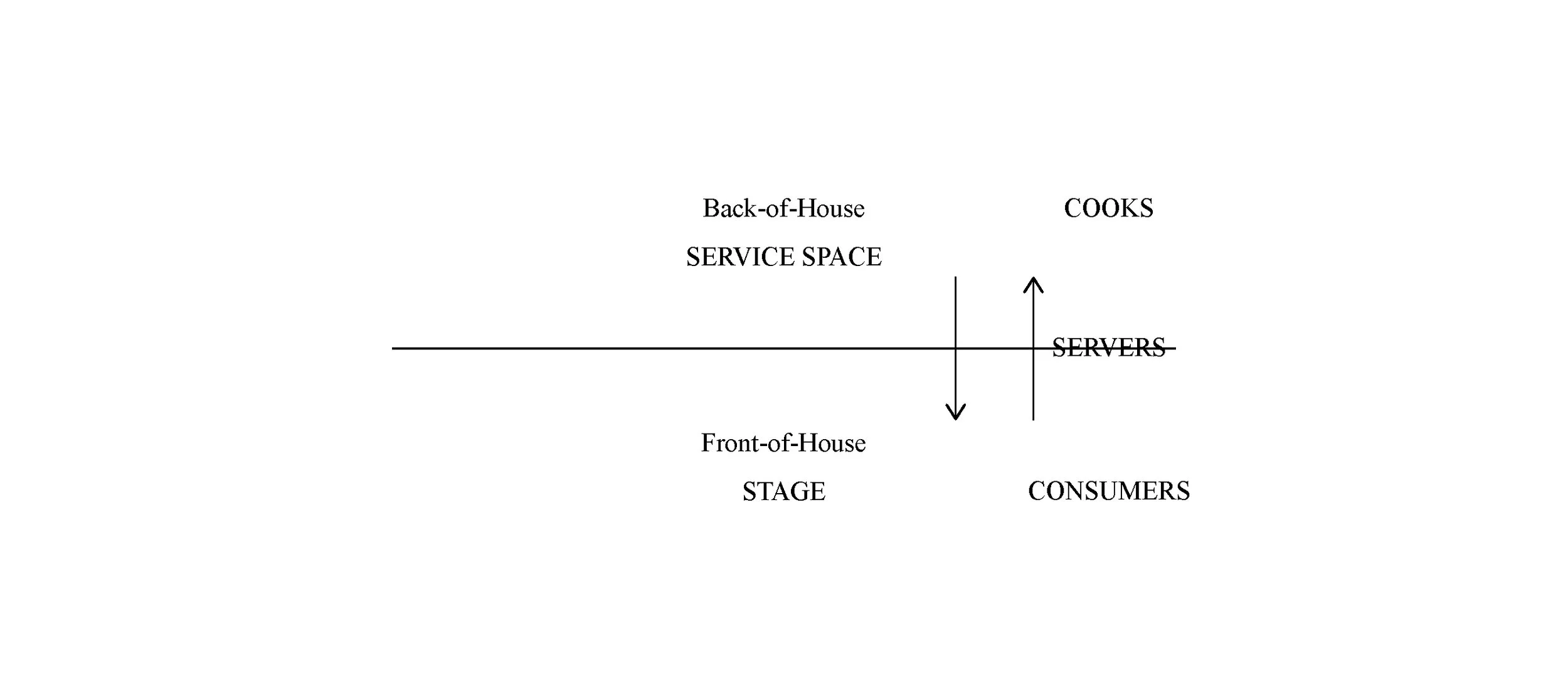

Figure 1: Diagram by the author.

As a programmatic typology, the restaurant separates consumer from cook, concealing labor in the back-of-house. The use of alleys, service doors, and freight elevators further invisibilizes service space, in contrast to the stage as a celebrated site of communal dining. Manhattan Chinatown’s oldest restaurants are a telling case study, where windowless basement kitchens are entirely opaque to the front-of-house, which is serviced by dumbwaiter (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Drawing by the author.

This concealment of service space can be traced back to the domestic buildings of aristocrats. Sociologist Sarah Bowen has stated that “in the past [not all] Americans were cooking their food. They were often relying on low-income women of color to cook a lot of it, and they still are. It’s just that it used to be in the house, and now it’s in restaurants.”(Pressure Cooker: why home cooking won’t solve our problems and what we can do about it. Oxford University Press, 2019. print.) Architect Mabel Wilson’s analysis of Monticello provides evidence of this typological lineage in plantations, where enslaver Thomas Jefferson “deployed the architecture convention of the section to place the spaces where enslaved people worked out of view. His placement of dumbwaiters near his fireplace made the work of Black servants invisible during intimate dinners.”(“Professor Works on Projects at the Intersection of Race and Architecture: Mabel O. Wilson co-designed the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers and co-edited Race and Modern Architecture” Columbia News. 15 October 2020.)

The treatment of hospitality workers and structures of inadequate wages today are descended from this country’s history of enslavement.(“Tipping, The Service Economy, and Anti-Blackness in the Hospitality Industry: A Mini Lecture by Ashtin Berry Feb 13th.” 13 February 2021.) That the design of restaurants reinforces existing social divisions has become more evident in the pandemic; “essential workers’’ continually risk their lives and health without government support while receiving hollow praise for their “heroism.” Elaborate architectural designs for outdoor dining have gone to great lengths to protect the consumer, a paying customer, while neglecting to take safety measures within the back-of-house. Ultimately, these staged precautions are ineffectual because servers are forced to indiscriminately interface with consumers and cooks, likely carrying the virus back and forth, underlining the hollowness of this spectacle (see again figure 1).

Foodways in Chinatown are informed by the neighborhood’s dual identity as a densely-populated and close-knit community, largely of elders dwelling in rent-regulated apartments and dependent on small mom and pop shops, and as a destination for outsiders, both tourists and diasporic Asian Americans. The architecture of Chinatown underscores this divide: the gilded restaurant interiors, highly aestheticized arches, and ornate building facades are designed with tourists in mind.(“Pagodas and Dragon Gates.” 99 Percent Invisible. 08 December 2015.) Meanwhile SROs, single resident occupancy hotels, still house much of the neighborhood’s population. These old buildings are difficult to navigate, according to mutual aid and food justice groups like Moonlynn Tsai and Yin Chang’s Heart of Dinner, which has regularly provided hot meals to Chinatown elders since the start of the pandemic. Design efforts favor the public-facing aesthetic expression of Chinatown, while spaces occupied by longtime residents are comparatively under-served.

Figure 3: Google Street Views curated by the author.

Architects are notoriously preoccupied with authorship and proprietary ownership of creative work, asserting aesthetic authority rather than grappling with the needs of a community. As designer Liz Ogbu stated last July, “the system is working exactly as it was designed, to service the few, to make the process transactional.” Architectural design is taught “as this ‘objective thing’ that ‘gets applied’” rather than acknowledging the individual biases present in every aspect of creative design work.(“What is Community-engaged design during - and after - COVID?” Center for Urban Pedagogy. 22 July 2020.) Though Chinatown’s restaurant kitchens are entirely underground, a hatch on the public sidewalk provides access. Interactions between restaurant cooks and passersby are frequent (see figure 3). This break between back-of-house service space and the front-of-house stage happens in the street, a notably public context, and subverts the typical division. Close observation of informal use of existing spaces by inhabitants offers insights that are crucial for contextually-specific and community-minded spatial designs. Following these indicators, architects can work towards challenging status quo hierarchies and societal inequities rather than reinforcing them.

FURTHER READING

Andrea Mubi Brighenti, Urban Interstices: The Aesthetics and the Politics of the In-between (Routledge, Taylor & Francis, Informa)

Patricio Davila, Diagrams of Power: Visualizing, Mapping, and Performing Resistance (Onomatopee)

Vittoria Di Palma, Intimate Metropolis: Urban Subjects in the Modern City (Routledge, Taylor & Francis, Informa)

Michael Sorkin, Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space (Hill and Wang, Macmillan Publishers, Holtzbrinck)